A generation of designer babies is both an exciting and a daunting prospect for scientists who dare to imagine a future free of genetic disease but can’t say how the effects of choice and accessibility will affect society.

Driving such innovation is CRISPR-Cas9, a technology that cuts and replaces faulty DNA in cells and has become more widely available and easier to use over the past few years.

“I believe everyone who works in a laboratory is looking forward to [CRISPR],” said Ludmila Volozonoka, a molecular geneticist at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom.

But as the scientific community celebrates, it also prepares to address the ethical dilemma of how much more it can — or should — manipulate nature.

“In general, yes, this technology will allow [scientists] to directly change the genetic information in the embryo. In my opinion, those are very rare cases when this can be applied,” Ms. Volozonoka said.

A fertility clinic in Ukraine, however, is boasting about its success in creating human embryos from the DNA of three people. The Nadiya Clinic in Kiev said it has successfully delivered four babies and that three women currently are pregnant using a procedure to create healthy embryos. Its scientists used the shell of a healthy donor embryo and filled it with the fertilized nucleus of the expecting parents.

“This procedure does not introduce any changes to the DNA,” Ms. Volozonoka explained. “It’s just a selection or non-selection of what nature has to offer for us.”

The Kiev clinic advancement shows how scientists are using innovative ideas for procreation. For many, the holy grail of fertility advancement is the ability to change DNA in the developing embryo, known as germ-line editing, with the potential to affect future generations and inheritable traits.

This is where CRISPR stands to make the most impact.

Discovered in the mid-1990s, CRISPR is a group of DNA sequences found in bacteria and viruses and offers a natural defense against bacterial infection. In 2012 and 2013, two groups of scientists worked simultaneously to harness CRISPR into a technology that could edit the genetic code by excising bad genes and replacing them with healthy ones.

This procedure changes the DNA of reproductive cells and therefore affects future generations and inheritable traits. The overall goal is to eradicate genetic diseases, but it offers the potential to choose or introduce specific genes for certain traits.

Last year, an international consortium of medical professionals published a consensus on the “science, ethics and governance of human genome editing.”

Of their determinations, it included that gene editing should be used for the treatment or prevention of disease and disability and that any “enhancements” should be weighed with public engagement and discussion, according to a review by the World Economic Forum.

Scientists are considering a number of issues, including whether the technology will worsen the divide in health care access between rich and poor, the ethics of editing physical traits and abilities, and the effects of gene edits on future generations, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Scientists are experimenting to determine best practices in gene editing, but countries have raised a number of barriers. In the U.S., federal dollars can’t support research that makes or destroys embryos. Some scientists will experiment on mice or zebrafish, which share many common genes with humans.

‘Still quite raw’

However, experimentation on embryos isn’t banned outright. In Oregon last year, privately funded scientists used CRISPR-Cas9 on human embryos fertilized with sperm with a genetic defect. Their goal was to replace the bad gene with a lab-manufactured healthy gene, although this didn’t happen. When CRISPR-Cas9 “cut out” the bad gene, the embryo replaced it with a healthy gene taken from maternal DNA.

The study was published in the journal Nature in August.

Although the experiment successfully used CRISPR to target a specific gene, it set back scientists with the idea that they could develop a library of desirable genetic traits to be inserted at the whim (and wallet) of a patient.

Yet scientists have had some success in somatic gene editing — changing DNA in cells that won’t be passed down through reproduction. The breakthrough occurred in 2015 in the case of a 1-year-old girl in England who was suffering from an aggressive form of leukemia. She received an infusion of genetically modified immune cells, and her cancer ultimately was cured.

Although scientists have not been able to tinker successfully with the genetic code in a developing embryo, their hope is that one day CRISPR-Cas9 can help improve and streamline efforts to develop babies that come from parents who both carry a genetic defect.

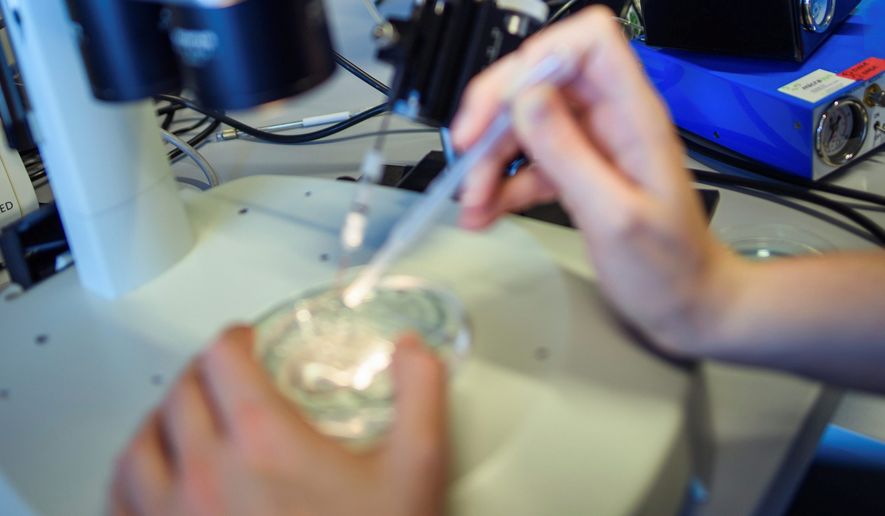

Today, couples who are both known carriers of genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Huntington’s disease, muscular dystrophy or sickle cell anemia can undergo in vitro fertilization, growing their embryos in a petri dish, so scientists can test for a wide range of diseases and choose the healthiest embryo to implant.

“In general, there are thousands of genetic disorders because our genome contains more than 20,000 genes,” said Ms. Volozonoka. “Each gene can have a mutation, which can lead to some specific syndrome. But we don’t know all those syndromes because they are very uncommon in a population.”

The potential with CRISPR-Cas9 is that it can streamline developing healthy babies by editing defective embryos instead of making many and seeking one without disease.

“I don’t think that this technology will come into diagnostics very soon because it’s still quite raw and only being tested in a scientific laboratory,” Ms. Volozonoka said. “But definitely this day will come.”

The pace of scientific discovery has jumped by leaps and bounds. Scientists analyzing human DNA can accomplish in 20 minutes what used to take two weeks, said Dr. Zev Williams, chief of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility and an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center.

With so many devastating diseases that scientists are continuing to identify or discover, taking the time to treat and master solutions for those problems takes priority over research on other gene-editing choices, he said.

“There’s sort of a theoretical discussion that arises on whether people want to [change eye color or hair color], but in practice, I just don’t see that happening,” Dr. Williams said. “It’s not like we have a shortage of really severe targets that we’re trying to cure.”

• Laura Kelly can be reached at lkelly@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.